Last year, a Harvard astrophysicist claimed to have found objects of extraterrestrial origin at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. If true, the discovery would open up the unnerving possibility that aliens not only exist, but could have visited us before. The leading research suggests, however, that these objects aren’t the stuff of cosmic horror but of something far more sinister: industrial coal ash pollutants.

Confusing a human-created material for an extraterrestrial gadget is, in many ways, understandable. Our constructions taken out of context are strange. But so too are millipedes. What qualifies as otherworldly depends, of course, on perspective and experience.

A place can only be considered “alien” in reference to a familiar baseline. That explains why images of the Atacama Desert look far weirder to most of us than strip malls, even though the latter is objectively stranger. And yet despite this subjectivity it feels as if there’s a collective alienation of Earth’s environments underway—a global weirding and a cultural severance from them.

* * *

Earth’s aliens arrived not by invasion but by invention. Industrial empires, climate change, and ecological ruin have fundamentally reshaped every coordinate of the globe into something new and unfamiliar. Interviews with survivors of climate catastrophe or journalists reporting on capitalist wreckage gravitate towards "otherworldly" as a qualifying adjective. What other word is better suited to describe liquified aluminum dripping from a car melted by wildfire or the skeletal crypts of bleached coral reefs? These sights, they suggest, are so strangely devastating that it’s hard to fathom they are of this Earth.

And they’re correct. In its simplest form, climate change is a set of numbers marking our deviation from the atmospheric and biological parameters that allowed civilization to arise. It is therefore a warning: stray too far from this habitable Goldilocks zone and that which you’ve built will crumble. Earth has been here before. Travel back some 600 million years ago and the planet was entirely ice. A few billion further and it was all molten lava. We’re discovering that anything beyond this comfortable 200,000-year present stretch is as inhospitable to human life as the surface of Mars.

In this way, the idea of Spaceship Earth is less an invitation to explore the stars and more a claustrophobic clusterfuck of steaming vents, closing airlocks, and mad dashes to the control room to stabilize our descent. With a pinch of effort and plenty of luck, we’ll land. Then comes the next problem.

* * *

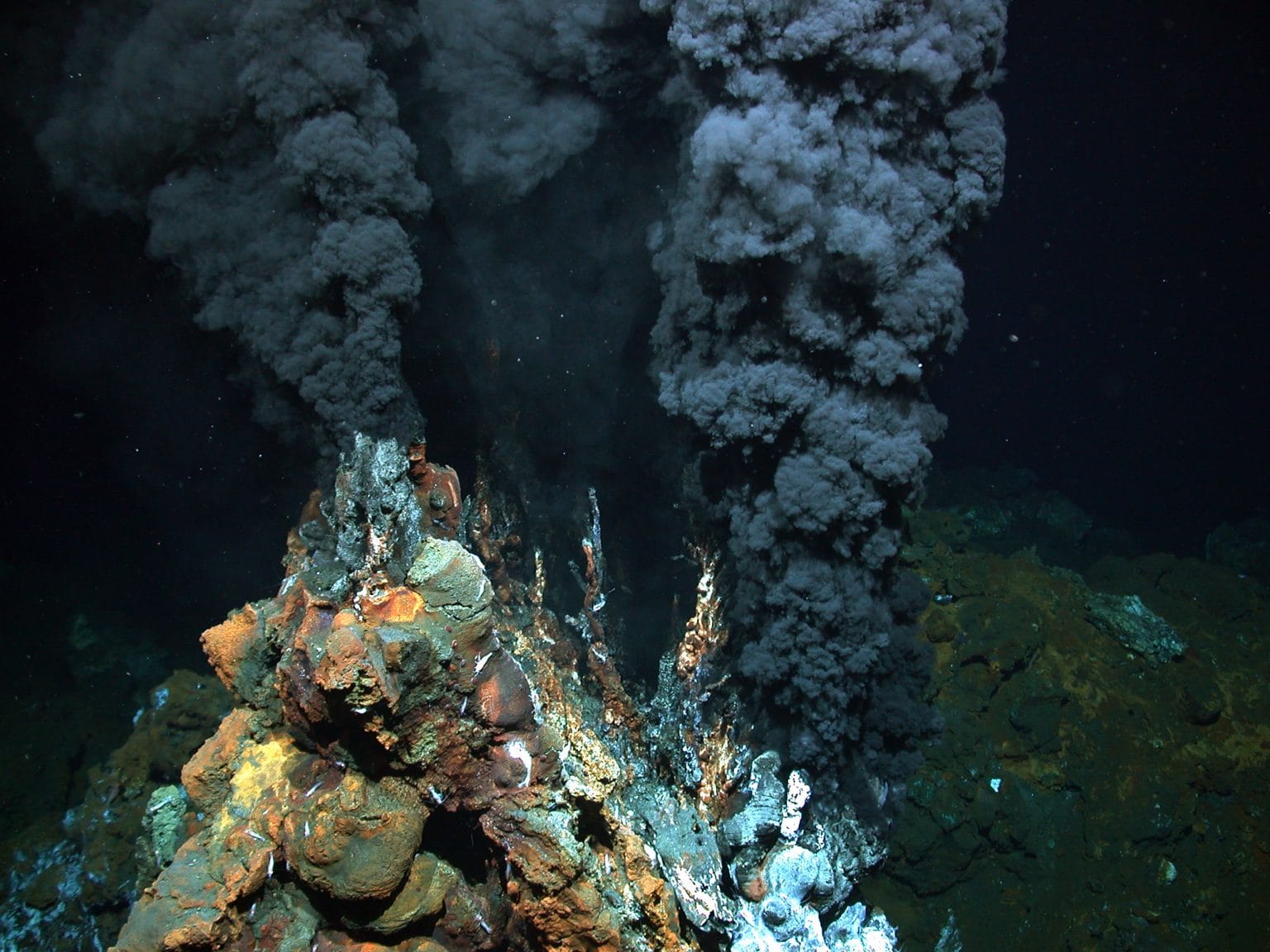

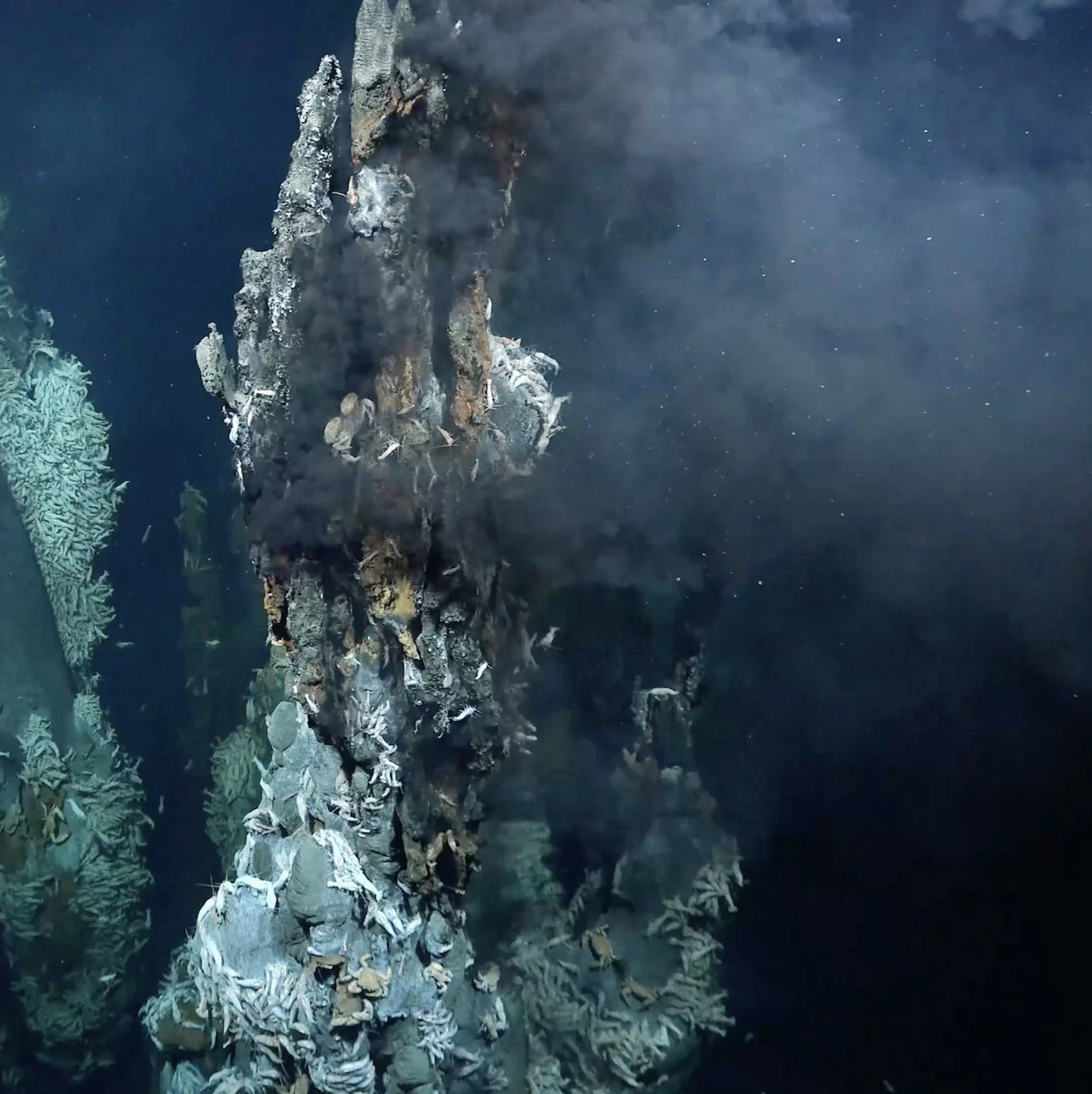

Had the Harvard professor searched near a mid-ocean ridge, he might’ve actually found alien life—or the closest there is to it. Deep sea hydrothermal vents are the most alien-like environment that could exist on Earth. Visited only by submersibles, these vents pump black and white plumes of sulfur and barium; volcanic cathedrals erupting in a darkness more complete than night. Life thrives here in the absence of photosynthesis. It’s thought that all life today can trace its roots to these boiling dark waters. And if the crustacean swarms and Pompeii worms make do, then perhaps life might just exist in the dark seas of Jupiter’s moon Europa. The only group more excited than the marine- and astrobiologists are the miners. For these deep-sea smelting towers contain critical minerals—lots of them.

Three images of black smokers taken by research submersibles and an image of a Pompeii worm (Alvinella pompejana)

Our species’ track record when confronted with the unfamiliar is damning at best. Our innate fear of the unknown translates to a damaging tendency to transform the alien into the familiar. During the colonization of North America, Amitav Ghosh writes about the English’s mission to terraform the land into familiar neo-Europes that suited European ways of life, itself a form of warfare via environmental manipulation. And, “consequently, narratives of terraforming draw heavily on the rhetoric and imagery of empire, envisioning space as a “frontier” to be “conquered” and “colonized.”

Centuries later and these colonially-terraformed landscapes continue to wreak havoc. A European approach to wildfire suppression (and general suppression of Indigenous practices) has contributed to the excess fuel loads that kindled a new era of Californian wildfires. On the other side of the country, invasive east Asian kudzu vines—alien-like in their tentacular swarm—have overrun native ecosystems and instill fears of choking infestation. America’s popular culture deems vine an invader and sterile lawns a sign of home.

It’s hard to find a foothold on land so fundamentally altered. The air’s a bit harder to breathe. The sun feels hotter than usual. We’re stepping out of the capsule onto new terrain and quickly finding ourselves in need of a space suit.

* * *

I write this from a non-native eucalyptus forest (planted by the U.S. army) with a selection of photographs I took of recently-melted glaciers in Svalbard (the fastest-warming place on Earth). At this point in time it’s hard not to find terraformed landscapes, and even harder to traverse familiar ones.

I find our response when confronted with alien landscapes confounding. Why do we protect Yellowstone’s tie-dye hot springs but mine deepsea thermal vents for minerals? Geologists often call this era the Anthropocene to signify the outsized role of human activity on the Earth, but at no point in history have we ever known ourselves less.

“Alienation” is rooted in the late Middle English word for “estrangement.” And, besides the violence of colonial terraforming, I think this is where much of the problem lies. For Earth’s landscapes turning alien and our species’ alienation from them are separate but connected issues.

Estrangement often leads to othering, terraforming, and exploitation. It’s the basis of disconnection. Most of us in modern society are so divorced from our material support systems that the minerals in our phone battery might as well have come from a passing asteroid. We’ve spent centuries alienating and abstracting the outdoors while acclimatizing the indoors that we’ve forgotten which is truly more otherworldly.

And for many of us attempting to overcome this separation by deepening our connection with nature, we’re finding it’s not as we remembered. Like the astronauts in Planet of the Apes, we’ve returned to a planet we don’t quite recognize. This glacier used to be longer, these corals not quite so white—did that primate always have a vengeful glint in its eye?

Can we counteract estrangement with our tendency to terraform the alien? If our innate fear of the unfamiliar catches up to the unfamiliar Earth we’re creating, then maybe we’ll reverse our systems to bring us back to that habitable Goldilocks zone. That solution, however, entails some degree of geoengineering: contentious high-tech solutions like stratospheric aerosol injection or reflective mirrors placed in orbit. Solutions, in other words, so far into the realm of science fiction that they risk even further alienation from the nature we know.

For now we seem to be stuck in a closed loop. It’s so hard to envision a different, better world that a growing number of people are seeking refuge in colonizing new planets. But that just shows our lack of imagination. Thinking we’ll be just as comfortable in a geodesic dome on Mars is like thinking industrial pollutants are the trappings of an alien.

Alleviating our alienation requires answering a question: is a particular landscape alien because it’s unfamiliar to us or because it’s genuinely gone awry? This is the difference between encountering a deep-sea geothermal vent versus a graveyard of bleached coral; the distinction between wonder and estrangement.

If we can’t separate from our terraforming ways then it only makes sense to bend it towards good. To invent new aliens that combat the old: gene-spliced bacteria to consume plastic or specialized rocks to remove atmospheric carbon. That world may ultimately feel unfamiliar to those of us alive today, but it represents an end to a harrowing voyage nonetheless. To arrive at a new Earth, crowded with aliens and strange encounters, wondrous in its own way, and with an atmosphere we can actually breathe.

* * *

Written and photographed (unless otherwise indicated) by Ryder Kimball

Member discussion: