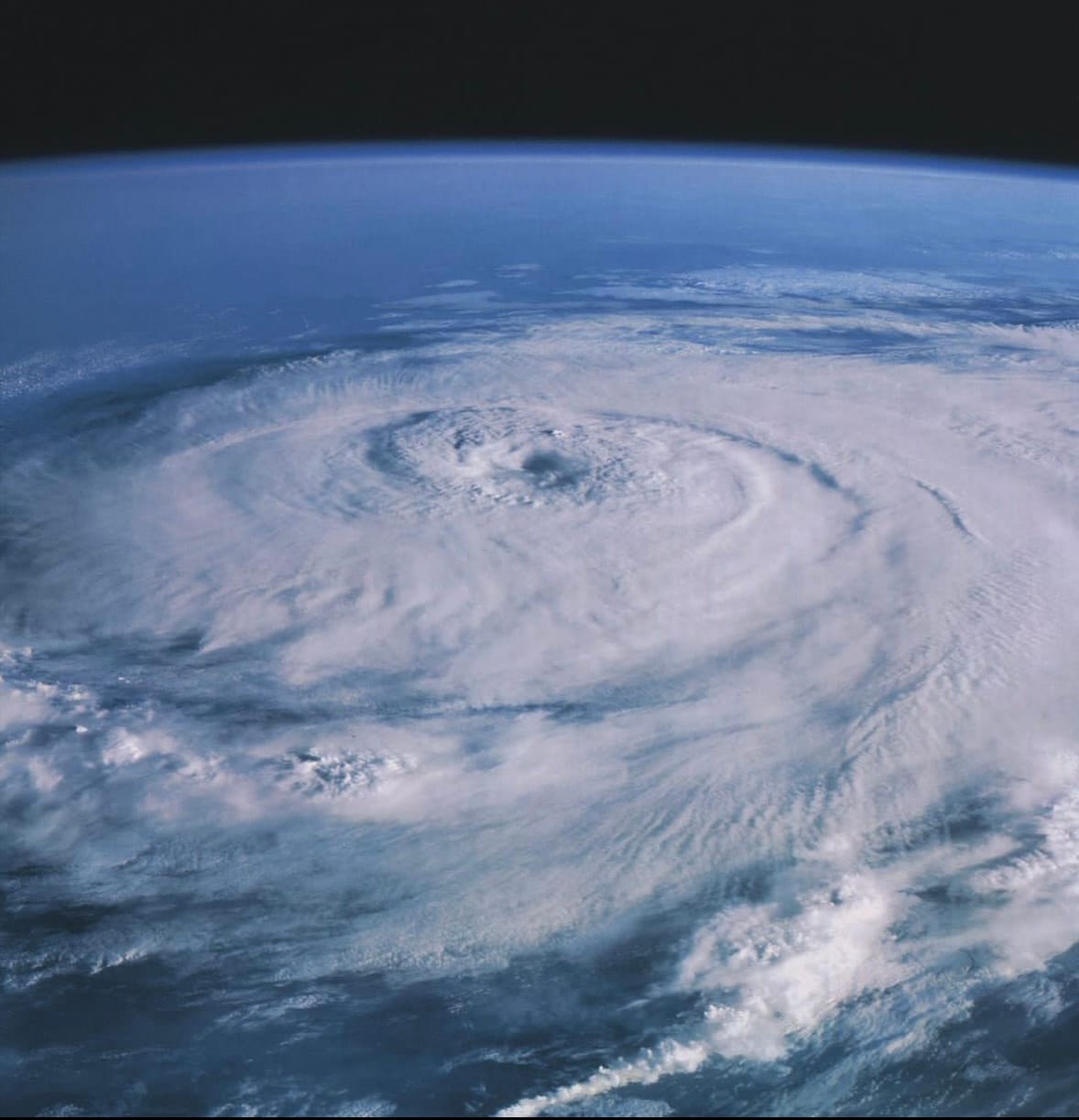

There’s a popular Tweet that’s gone viral during recent catastrophic weather events. It reads: “climate change will manifest as a series of disasters viewed through phones with footage that gets closer and closer to where you live until you’re the one filming it.” It’s pithy and true. Climate cataclysm will, sooner or later, reach us all.

But before it’s your unenvious turn to pull out your camera and hit record, there will be a notification and an alarm. An emergency one. It should inspire a degree of terror the first time you hear it—that’s what it’s designed to do. But when it inevitably rings again years, months, or—increasingly likely—days later, the emotion it may elicit is far more sinister: complacency.

The Emergency Alert System (EAS) is arguably the government’s best tool to rapidly provide people information on an impending disaster. What began with Paul Revere on horseback has evolved into the likes of civil defense sirens and TV broadcasts. The latest iteration—brought to you through your phone—acts like a techno song: succinct and repetitive text scored by abrasive noise with the implicit appeal to move your feet.

One of the few actions an individual can do to avert a weather-related disaster—at least in the short term—is to move out of harm’s way. But as climate change supercharges their frequency and intensifies their impact, the number of emergency notifications is rising so sharply that, as Zoë Schlanger reports, alert fatigue is already setting in.

The latest emergency alert in my phone reads “TSUNAMI WARNING.” The one from two weeks prior says “TORNADO WARNING.” A few hundred miles south in Los Angeles, the advanced warnings of wildfire’s rapid movement saved lives. For now it’s one of the few areas of climate communications that work. But as the frequency of disasters rises and trust in media platforms disintegrate, some are already acclimatizing to the blaring toll of the climate apocalypse’s seven trumpets. Others are just hitting snooze.

* * *

EAS alerts have worked so far because they match a palpable concern to a decisive action. The alarm + instruction experience is still a novelty. But with each alert that fails to materialize and every spike of adrenaline with nowhere to go, we lose yet another precious resource: fear.

Most of us have failed to convert the existential terror of climate change into the physical consequences threatening us now. Its impacts are often abstract, distant, and poorly-represented. We remember the handful murdered by Jack the Ripper but not the thousands killed by the Great Smog of London because a shadowy man with a knife is a more salient symbol of fear than an anticyclone trapping industrial emissions at ground-level.

And when that existential terror does manifest itself closer to home, like the devastating scenes of fire-blackened ruin in Los Angeles, we’re left with little time to process before the next event strikes. But our minds can’t operate in a constant state of fear, so we break the doomscroll with stories of hope. Until our attention—that other precious, dwindling resource—cycles back to the weather’s latest lash… “with time, vigilance tends to relax, because all horrors are dulled by routine.”

Is there, then, a way we can preemptively prepare for the alert fatigue and design a system that lasts, one that can perpetually trigger our fear response when it matters most but without crying wolf?

* * *

“Sending this message was important to us. We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture… This place is not a place of honor… no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here… nothing valued is here. What is here was dangerous and repulsive to us.”

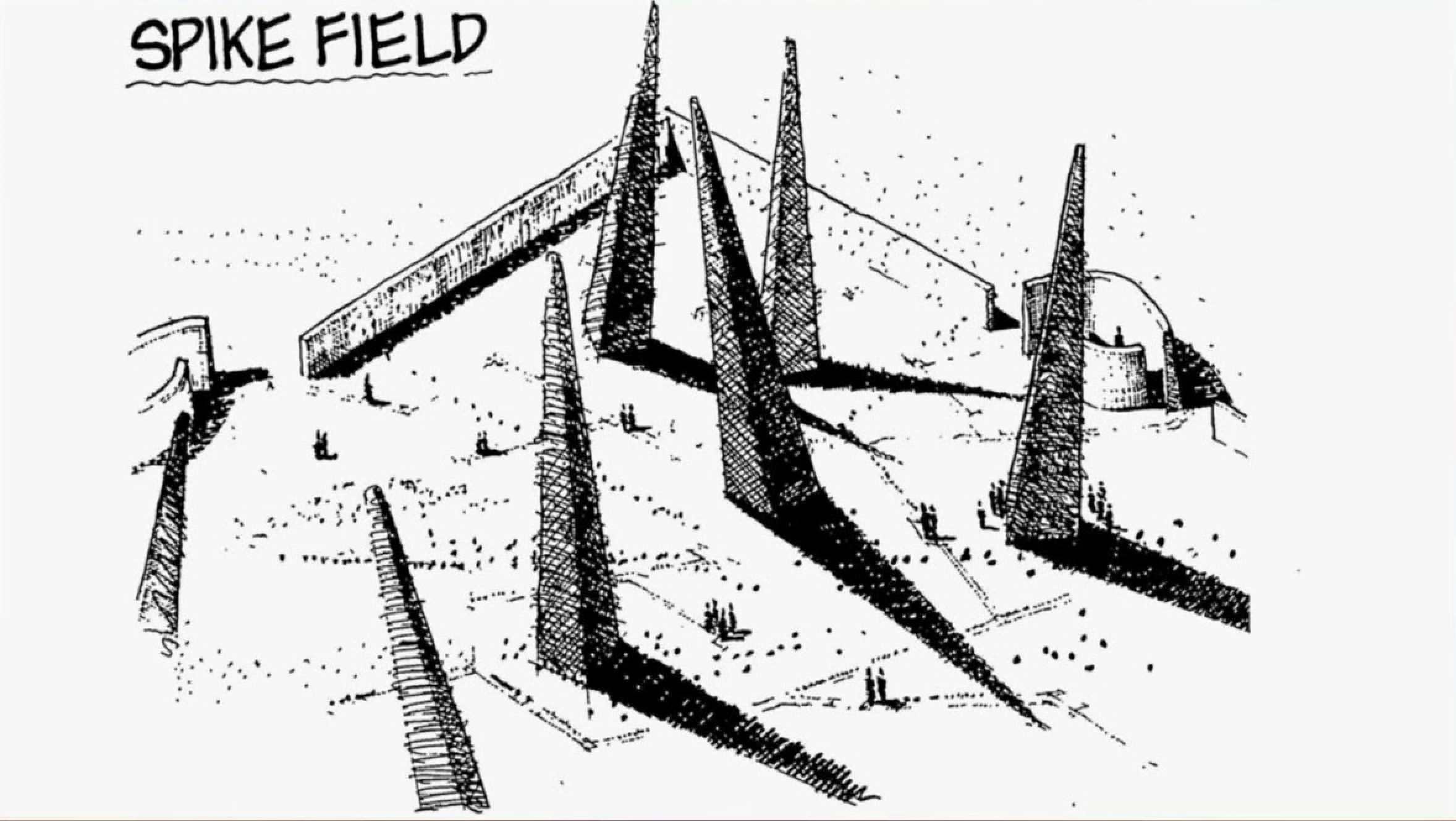

How do you communicate that a buried tomb contains an ancient affliction, a curse of sorts, for a span of 10,000 years? Do you write out the warnings in a smattering of languages in the hopes that future generations can decipher them? Do you make the mausoleum’s architecture so imposing and physically threatening that it fills any wanderer with dread? Or do you genetically modify cats to glow in its presence and anoint a priesthood to interpret the bioluminescent fur like scripture? The answer, it turns out, may just be all of the above.

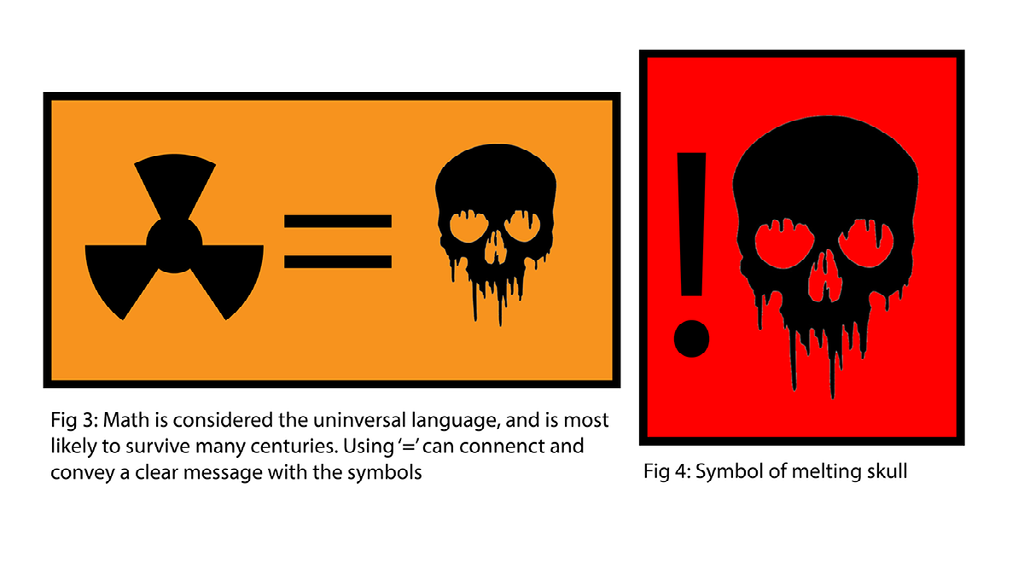

In 1945 the world was introduced to a particularly acute form of annihilation in the atomic bomb and years later its stagnant, but no less ruinous, counterpart of nuclear waste. The accumulated material posed an intractable communications dilemma: humanity’s language and symbols evolve on orders of magnitude less than the material’s radioactive lifespan. (Not convinced? Try reading the 1,000-year-old Beowulf in Old English).

In something akin to an Ocean’s Thirteen-themed plot for sci-comms nerds, The Department of Energy assembled a task force of linguists, archaeologists, and climatologists to break into that labyrinthian bank of human stubbornness and figure out how to overcome our innate curiosity. The field of research they devised is called “nuclear semiotics.” It incorporates writing, symbols, audio landscapes, architecture (like spike fields), and myths to create an enduring fear of an entity hard to comprehend, lethal, and largely invisible.

It’s impossible to prove the effectiveness of long-term nuclear waste messages for another few thousand years. But I’d wager you wouldn’t wander past multiple hazard symbols and the insectoid click of a Geiger counter for a gander at some dying uranium. The success of nuclear semiotics is evident in our hesitation around and fear of radioactivity. And if there’s another force equal in terror to the sun’s ripping of atoms, it’s the wrath of the carbon-charged Earth.

Climate change most desperately needs a lobbying firm, but after that it could use a PR team too. One that could build a system of semiotics to communicate not only the path of a storm but to also continually convince people to move out of its way. To emotionally equate 9 millimeters of additional rainfall to a 9 millimeter bullet. To create an ecosystem of fear interlinking its forecast of destruction. A communication system that leverages every page in the horror playbook to haunt each of us and ensure that our baselines don’t shift—for what’s happening is not normal, and it is nothing short of utterly terrifying.

I’m talking of curating a very specific type of fear: not fear of the planet itself nor a paralyzing terror that leads to inaction. But an eerie one closer to the Lovecraftian horror of encountering an entity uncannily colossal, violent, and entirely indifferent. A fear borne of respect and humbleness—God-fearing, perhaps. A recognition that our millennia-long efforts to tame the wild are backfiring. To conjure that primal memory of a life-giving yet unforgiving Earth, still there, just below the surface.

In mountaineering the term is called exposure—sections of a route where a single, simple misstep can be catastrophic. Our exposure deepens with each life support system we tear away from the Earth and each further step we take teetering through tipping points. Perhaps a new field of ‘climate semiotics’ can strengthen the awareness of our fragile foothold on this hurtling rock and engender a new generation of Earth-fearing stewards. It may just help us listen when the alert rings once, twice, then again, and again.

When it’s your turn to film the next disaster, will your camera shake as you run for your life or as your hands tremble with fear?

Written and photographed (unless otherwise indicated) by Ryder Kimball

Member discussion: